Book of Doubt / Book of Faith: A New Secular Sacred Work

by ADAM ROBERTS

When Alex Weiser (composer, and program director at YIVO) called me last November to offer me a commission to write a new work for chorus, percussion, and viola, I was honored to be asked and excited that my new piece would be premiered alongside Morton Feldman’s Rothko Chapel and David Lang’s The Little Match Girl Passion (I’ve loved the former for many years and have recently gotten to know and admire the latter). I was also intrigued by the title of the program, “secular sacred music,” a topic about which I felt I had something important to say. But I was terrified because my wife was seven months pregnant with twins (our first babies), and still needed to move from NYC to Ohio, where I had just taken a teaching job at Kent State University, and I was worried I wouldn’t be able to write the piece I wanted to with the challenges that lay ahead. I asked Alex if we could do the concert next season, but for pragmatic reasons that was not possible. So I agreed, hoping that my creative process would cooperate and assist me in making the piece I wanted to write.

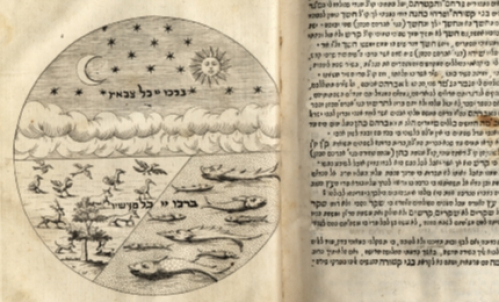

“Secular sacred” is a rich and thought-inducing prompt. At first it may seem like something of an oxymoron, but of course it’s common now for people to claim to be “spiritual” without committing to a belief in G-d or to be practitioners of a religion. It’s a phrase that seems particularly appropriate for the wide range of ways of identifying as Jewish, from “cultural Jews” on the one hand to the more orthodox on the other. I’ve long connected to the concept of tikkun olam, the importance of repairing the world, and its social justice associations and ramifications; such an ethic without a requirement of identifying as “religious” is perhaps one particularly Jewish manifestation of the concept of the “secular sacred.” Morton Feldman’s approach to art might be another version; his work emanates an aura of spiritual intensity without being about anything extramusical, let alone anything specifically religious.

I felt especially pulled to do this project because of my personal history and the perspective that results from it. I was raised by Jew-Bus (Jewish Buddhists), who had eschewed the practices of Judaism for a commitment to a daily meditation practice and an ethical way of life (vegetarianism, abstaining from alcohol and drugs, among other things). In this sense my family always felt “spiritual” to me, and my parents were serious meditators, practicing a couple of hours a day to this day, which separated them from their hippie peers who dabbled in psychedelics and meditation but were less rigorous in their practice.

This way of life marked me early. I was a vegetarian with a laundry list of items I couldn’t eat tattooed to my preschool lunchbox. And though my parents’ path included a serious commitment to spirituality, our lives were devoid of outward ritual (the meditation practice they do is a solitary one and other rituals are considered inessential). I was taught I was Jewish, but only because my mother wanted me to know that being Jewish came with consequences since the world was not always kind to Jews. We enacted an arts and crafts version of Hanukkah as the celebration of light, and I slept through high holidays at my grandmother’s house with extended family. We were the only ones out of my cousins who were not bar/bat mitzvahed. It wasn’t until many years later that I started to consciously identify as Jewish through my experiences as a musician. When I was 16 I complained to a Jewish piano teacher at a summer camp about being deathly nervous to perform, and she told me it was in my genes (and not to waste money on therapy on it since it was inevitable). As a student at the Bowdoin Summer Music Festival at 21, I connected with other Jewish musicians and we put on a concert of Feldman’s music. My Judaism was constructed as an identity around music, art, intelligence and wit, sharp humor and a commitment to questioning life.

“Spirituality,” to me, on the other hand, has always been about direct experience through meditation and not about ritual of the kind that Judaism emphasizes. I made this point to Rabbi Felicia Sol, who married my wife Vicki and me last summer, and she made the point that while spirituality is indeed universal, we live through specific identity. The polarity of the universal to the specific is a compelling concept, and I’ve started to come to appreciate specific ritual as well (Vicki and I have been experimenting with having shabbat dinner with our babies).

So when I agreed to write this piece, my thoughts were swirling with reflections on the meanings of spirituality, ritual, ethics, belief, and Jewish identity. Most urgently, I needed to decide if I would be setting text, because if I were I would need to find that text before diving into composing, and time was short. The Feldman, like most of his works, is about sound, pattern, and is wordless, while the Lang sets a libretto he wrote, adapted from the Hans Christian Anderson tale. My music, like Feldman’s, focuses on timbre, but unlike Feldman’s music mine tends to be much more gestural and forward-moving. I decided I wanted a text, and one that would be evocative, but not too pictorial or clutter my musical landscape with too many specific extramusical associations.

I immediately thought of friend and poet Claire Schwartz. I told Claire about the project and asked her if she would be interested in writing, as I put it, “secular, modern, feminist psalms, that do not specifically reference G-d.” To my delight, Claire agreed, and didn’t change her mind when I told her I’d need the poems in a matter of weeks. Because of this constrained time frame, Claire decided to send me a poem a week.

I was floored by the first poem when I received it:

[First Person // Psalm on the Occasion of Creation]

And from the darkness, the word.

In the word, the narrow place: I

I I. From the narrow place, a bridge.

I seek the sea. Word for moonbeam, word for salt.

Who gave the first name? And with what wind?

Loneliness, my bride. And Nothing.

It was the poem I would have written if I could have; beautiful as a piece of abstract language, and pointing to both the creation story as well as “Nothing,” which for me connects to the “emptiness” of Buddhism. Claire outlined the following plan for her poems:

1. first person // [psalm on the occasion of creation]

2. second person

3. exile

4. construction of the temple / sacrifice

5. destruction of the temple / prayer

6. benediction

Claire’s plan was both a ritual in its construction and the story of the Jewish people told through beaming, pristine, abstract language. She decided to call the collection, “book of doubt / book of faith” and I simply stole that for the title of the whole work. In the end, Claire followed the plan with the exception of the sixth movement, which she didn’t end up writing, as the collection felt complete to her after “destruction.” I ended up adding a wordless interlude between “construction” and “destruction,” music that I had sketched in the very beginning of my creative process and which I titled “interlude: lullaby” and dedicated to our newborn twins, Aiden Daniel and Alexandra Rose Roberts. The lullaby is music I simply wanted to write, but also provides a moment of rest after the sacrifice and before the invention of prayer (“invention of prayer” eventually replaced “prayer” in the title of the last movement).

The rest of the poems are as striking as the first. Capital “N” “Nothing” makes several appearances throughout the work, offering opportunities for rescoring/connections. The language is terse, vivid, focused, and at turns specific and abstract.

The first and last movements are the longest, at seven and five minutes respectively, and are the most forward-moving, ending in a different place from where they each began. The middle movements, with the exception of the lullaby, are tense miniatures, and I think of movements two, three, and four as a triptych.

Though the challenges facing the creation of this piece were substantial, I felt a sense of serendipity throughout working on it. Claire’s work and the start of my family played a role in inspiring and birthing this piece. Now I look forward to the premiere.

This event is part of the Smithsonian Year of Music. For more information, please visit music.si.edu.

Adam Roberts writes music that takes listeners on compelling sonic journeys while drawing on a vivid array of sonic resources. Roberts’ music has been performed by ensembles such as the Arditti Quartet, the JACK Quartet, le Nouvel Ensemble Moderne, the Callithumpian Consort, Earplay, andPlay duo, Transient Canvas, Ums ‘n Jip, Fellows of the Tanglewood Music Center, the Boston Conservatory Wind Ensemble, the Association for the Promotion of New Music, violist Garth Knox, Guerilla Opera, and at festivals such as Wien Modern (Vienna), Tanglewood, the Biennale Musique en Scene (Lyons), and the 2009 ISCM World Music Days (Sweden).

Roberts is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, Fromm Foundation Commission, the Benjamin H. Danks Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, an ASCAP Morton Gould Young Composer Award, the Bernard Rogers Prize (Eastman), the New York Bohemians Prize (Harvard), the André Chevillion-Yvonne Bonnaud Prize from the Orléans Piano Competition, the Earplay Donald Aird Award, the Christoph and Stefan Kaske Fellowship from the Wellesley Composers Conference, the Leonard Bernstein Fellowship from the Tanglewood Music Center, the Blodgett Prize (Harvard), and other awards. Commissions have come from the Callithumpian Consort, the Boston Conservatory Wind Ensemble, pianist Nolan Pearson, the Tanglewood Music Center, Guerilla Opera, and others.

Roberts’ music has been called “a powerful success,” “arresting,” and “amazingly lush,” (the Boston Musical Intelligencer), “an attractive mix of the familiar and exotic,” and “otherworldly” (Boston Classical Review), and “invigorating” with a “persistent melodic urge” (American Academy of Arts and Letters citation).

Roberts obtained his Bachelor’s degree in composition from the Eastman School of Music in 2003 and his Ph.D. from Harvard University in 2010. Roberts also studied at the University for Music and Performing Arts in Vienna from 2007-2008 on a Harvard University Sheldon Traveling Fellowship. Roberts’ primary teachers have included David Liptak, Augusta Read Thomas, Julian Anderson, and Chaya Czernowin. Roberts has taught at Harvard University, Northeastern University, Istanbul Technical University’s Center for Advanced Studies in Music, and the University of Georgia’s Hugh Hodgson School of Music. He is currently Assistant Professor of Composition at Kent State University.