The Third Annual Carnival of the Big Stick

by HALLEL YADIN

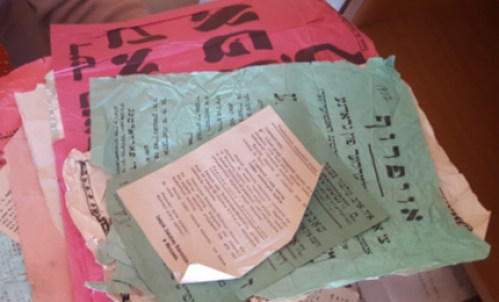

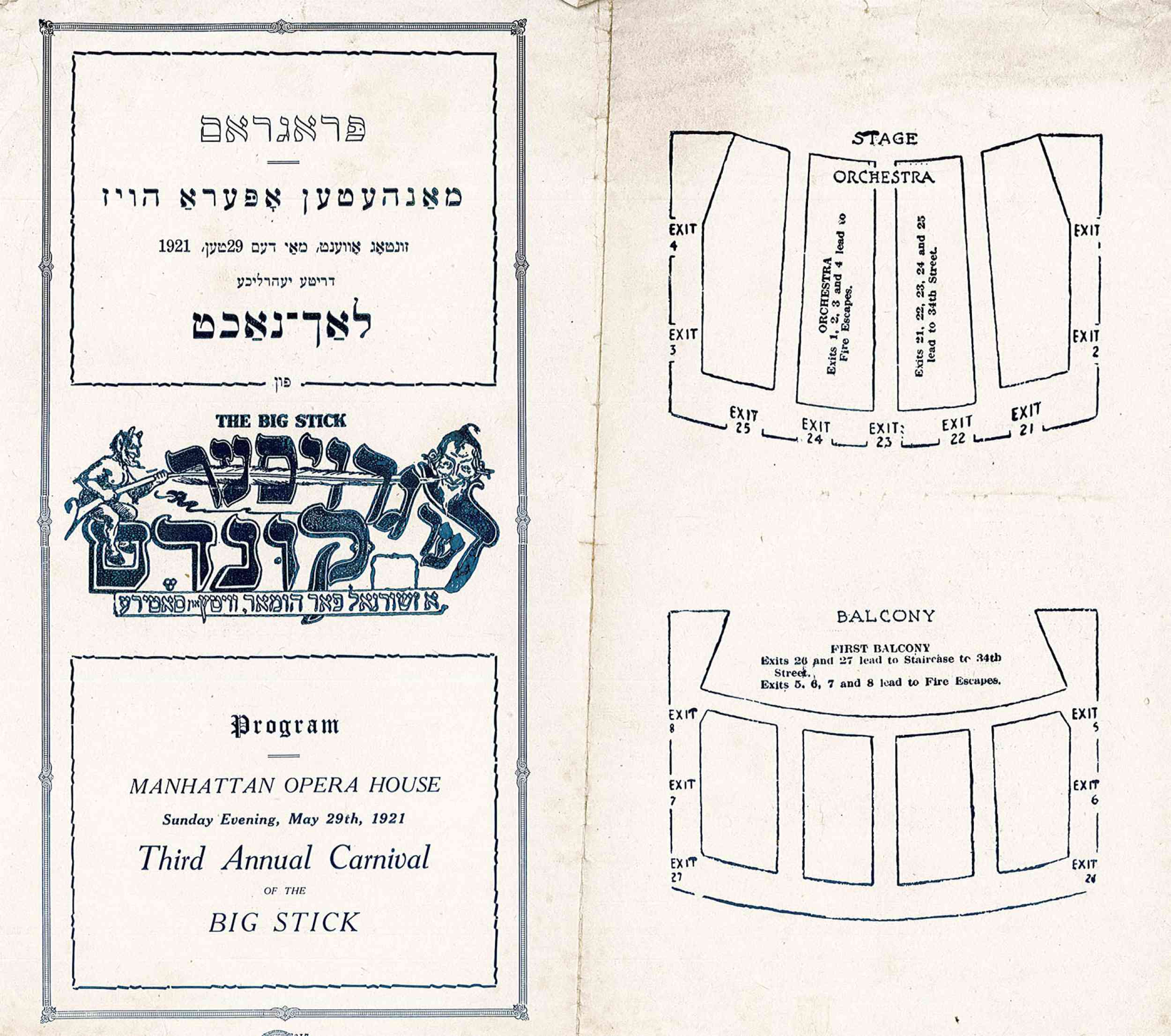

When I first encountered a program for the Third Annual Carnival of the Big Stick, I was unsure what to make of it. My first thought was that a Carnival of the Big Stick might entail a woodsy hike, or possibly a school supply convention that sold meter sticks à la the Scholastic Book Fair, but neither of those seemed likely. I discovered that this carnival was an event hosted by Der groyser kundes (The Big Stick), a satirical Yiddish weekly published in New York City from 1909 to 1927.

We can glean a good deal of information just from the program. Based on the date, May 19, 1921, this Carnival may have been related to Purim, a holiday for which historically Eastern European Jews had “enacted ritualized subversions of the official worldview and social order” — a goal not unlike the broader one of Der groyser kundes. The program features the Der groyser kundes logo, which is a satyr poking a man with, well, a big stick (specifically a big quill feather), which demonstrates that the goal of the publication was to use satire to give people a prickly little nudge. Finally, the Carnival was held at the Manhattan Opera House. There is an interesting contrast between the Manhattan Opera House’s genteel image and Der groyser kundes, which was decidedly unrefined.

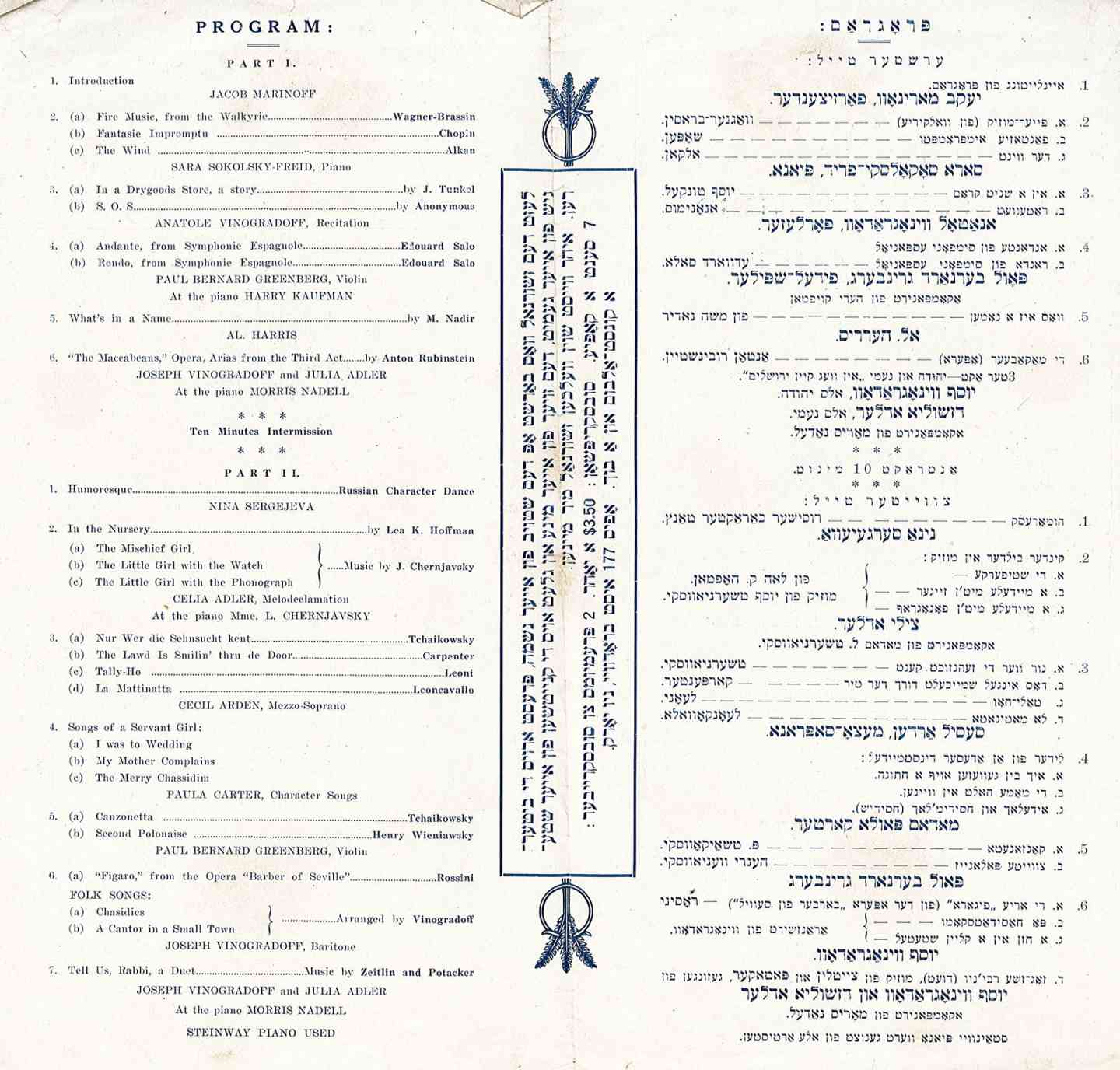

The program lists some historically significant performers, including Julia Adler, Celia Adler, Mme. Leo Cherniavsky, and Cecil Arden. This may give insight as to how this program ended up among theater artifacts in YIVO’s Vilna Collections. While the Carnival of the Big Stick was not a play, strictly speaking, it overlapped with New York City’s theater scene. Showrunner and Der groyser kundes editor Jacob Marinoff’s sister was Broadway actress Fania Marinoff, and his brother-in-law was controversial Harlem Renaissance novelist and photographer Carl Van Vechten. While I don’t know for certain, they may well have collaborated; Yiddish culture in New York in the early twentieth century was very much a part of the overall cultural landscape in the city.

The Carnival of the Big Stick (and one Concert of the Big Stick) is referenced in New York City newspapers in 1919, 1922, and 1924, so it seems that the Carnival was a recurring event. The Carnivals are advertised alongside plays, further indicating that they were associated with the theater scene. Details about the festivities emerged from unexpected places. For instance, the 1920 volume of the American Chess Bulletin reported that two of its Manhattan-based members entertained a crowded house with a living chess game at that year’s carnival.

Der groyser kundes was part of a larger scene of New York City-based Yiddish periodicals. As archivist Aaron Rubinstein writes, “By the time Marinoff’s Kundes was founded in 1909, the Yiddish press was reaching its zenith as the most powerful Jewish institution in America. As well as providing Jews contact with the world, the Yiddish press served as a Jewish ‘community center’ where Jews could gossip, get advice, be entertained, and express political opinions.” Der groyser kundes is also part of the long, rich history of Yiddish satire. The Carnival of the Big Stick would have brought those traditions to life in the vein of the Yiddish theater scene in New York City. Yiddish theater served as a social experience, a release for the weary immigrant laborers who made up so much of New York’s Yiddish-speaking population. While the Carnival of the Big Stick was not a play per se, it is easy to imagine that it might have served some of the same roles within its context as a satirical entity. Without knowing many specific details about this Carnival of the Big Stick, we can still infer that it was symbolic of several important elements of Yiddish culture in New York City in the early twentieth century, all mixed up in a communal event for its participants.

Still, life at Der groyser kundes was not always rosy. In 1912, its writers went on strike, arguing that they were underpaid at salaries of nine to fifteen dollars a week (very roughly the equivalent of $200-350 per week today). “[Marinoff] gives out comic ideas,” wrote The American Hebrew & Jewish Messenger, “which his underpaid writers take with them to a well-known coffee house where they whip them into shape for publication, inspired by weak tea and celery tonic.” Ashes to ashes, media unrest to media unrest, celery juice to celery juice.

Hallel Yadin is the YIVO Archives Associate.

Bibliography

A “Comic” Strike. (August 23, 1912). The American Hebrew & Jewish Messenger, 441. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/880930231/85737C6E449F44D8PQ/8?accountid=10368.

Epstein, S. (n.d.). Purim. Retrieved from http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Purim.

Friedlander, Y. (n.d.). Satire. Retrieved from http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Satire.

Living Chess in New York. (1920). American Chess Bulletin, 17, 100. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=2R8EAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Rubinstein, A. (Spring 2005). Devils & pranksters: Der groyser kundes and the Lower East Side. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20060505151924/http://yiddishbookcenter.org/pdf/pt/47/pt47_kundes.pdf.

Steinlauf, M. C. (n.d.). Yiddish Theater. Retrieved from http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/theater/yiddish_theater.