Interview 2: A. S-G.

I worked alongside Antanas Ulpis for many years. My work at the Book Palace [Book Chamber of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic] began in 1953. When I first set foot in this palace (built back in the sixteenth century by Carmelite monks) in search of the Book Palace Director, A. Ulpis, I was very surprised to discover, sitting in a small work room among huge piles of dusty books, quite a plain-looking, sincere man. That was how I saw Antanas Ulpis, director of this palace, who was very reluctant in accepting me for the job, because I had just enrolled at Vilnius University and could only work after class, and he needed someone to work full-time.

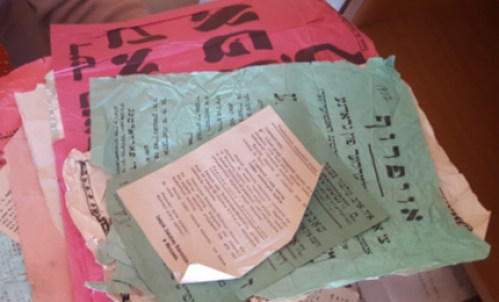

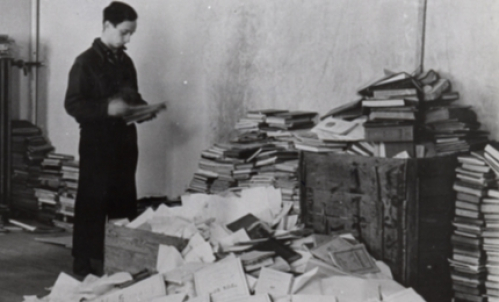

Since the very first days I was surprised by Ulpis’ simplicity, his greatness, his unbelievable determination and amazing willpower. I then learned that he had started working with just one small room and a chair. The institution did not even have a table in its earliest days. In other words, he had begun at zero. By my time, the institution had already taken form. I joined a large team, an international team, because people of different nationalities worked here: Lithuanians, Jews, Russians, Belarusians. Each had their own place, each did their own job. Thanks to his phenomenal personality, Ulpis managed to weld together a team that felt like a family, regardless of differences in nationality, intellect, or erudition. Then I found out that the Book Palace’s team had started out by traveling around Lithuania, going through all sorts of plundered mansions, churches, and libraries, collecting materials and publications otherwise doomed to be destroyed. All of these things were brought back to a place that was not even suitable for books, with the idea that one day the books would be saved, organized, would not be lost.

I should say that this was a dangerous job for its time. Even Ulpis himself often complained that nobody understood him and that he was risking a great deal. But he was a strong person. He had loved books wholeheartedly since his childhood and did not care about the language or the contents, just as he did not care about the political opinions of the people employed in his institution.

It was very easy and pleasant working with Ulpis, because he did not just love books: he also really loved people. I can illustrate with some examples. I have already mentioned that people of varied nationalities and political opinions worked with us, so there was a former nun employed in the same editorial office as me, a troubled woman who had her own opinions and never tried hiding or denying them. Very often, when preparing Polish print materials for a bibliographic publication, she would write descriptions that went at odds with the official position. In other words, she often wrote that an article was tendentious and biased against Catholic priests. Ulpis would react very calmly. He would invite me and quietly ask that I edit the annotation, without taking any repressive action against the woman. He would explain that this was her way and we had to accept her as she was: a fair, honest person, incapable of lying, who was writing the way she saw things.

Ulpis liked unique personalities, so he hired various poets, writers, and scholars who had been unable to carve out a niche in society. He would always ask us to be tolerant of those people, and instead of hurting them, to understand and respect them.So, we worked for many long years as a family.

As for the collection of old books, Ulpis spent lots of time working on them. Wearing a simple work smock, he would spend entire days and even nights, in the church where the books were piled, poring over them and complaining that he did not have enough energy to sort them all. However, he was absolutely convinced that the time would come when those old and seemingly unwanted books would be sorted and all the work acknowledged. Well, the saying that books have their own fates just like people proved true. Ulpis’ fate was the same.

Many years later, his hard labor, his efforts, his modest and unrewarding work have finally received appreciation. Being a good, honest person and valuing these traits in others, Ulpis was able to work both with people and with books.

Many things could be said about Ulpis. He was not merely a man of books. He had very broad views. For instance, he enjoyed music and art, so visits by famous singers and performers were frequent. Fascinating events took place in these old halls, under these domed ceilings, and it seemed that the old times were coming back, when people used to play music in private chambers in manors. He knew how to combine work and rest.

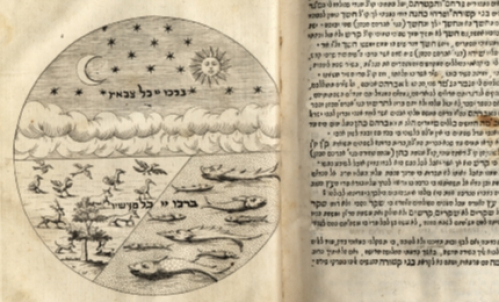

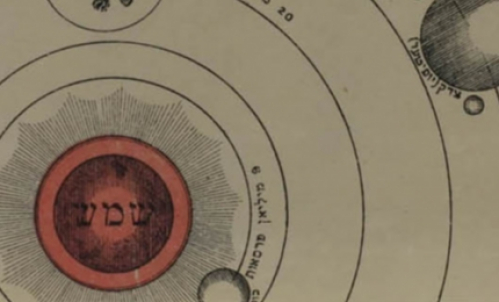

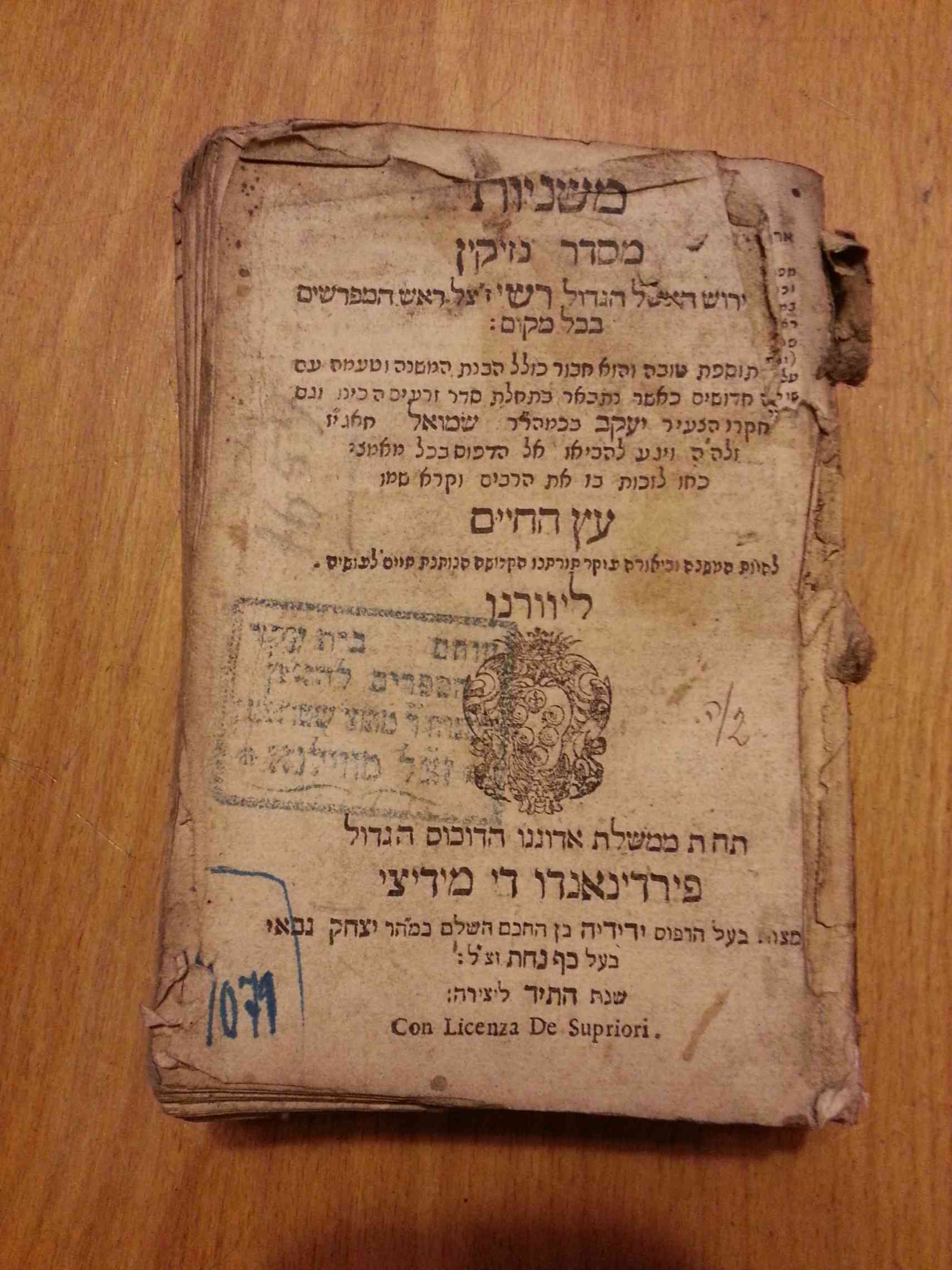

As for the Jewish collection, I know little about it, but ever since my first days here I heard from Ulpis that he had saved it. Although many disagreed with the decision, Ulpis was a brave man. He was convinced that the work was necessary and that a book, whatever may it be, in whatever script it was written, was a precious treasure of Lithuania and all mankind. He was able to argue this position without fear of losing his good name or anything else.

Today we are finally able to appreciate Ulpis’ determination, bravery, and honesty. It is probably symbolic somehow that the Jewish collection was concealed for so long in an old Carmelite church.