Interview 4: M.U.

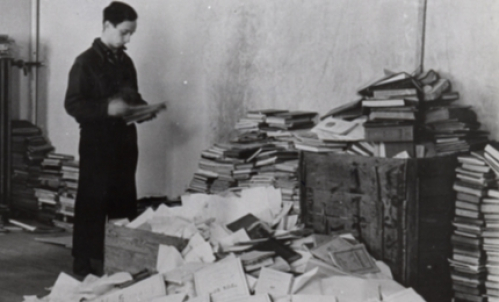

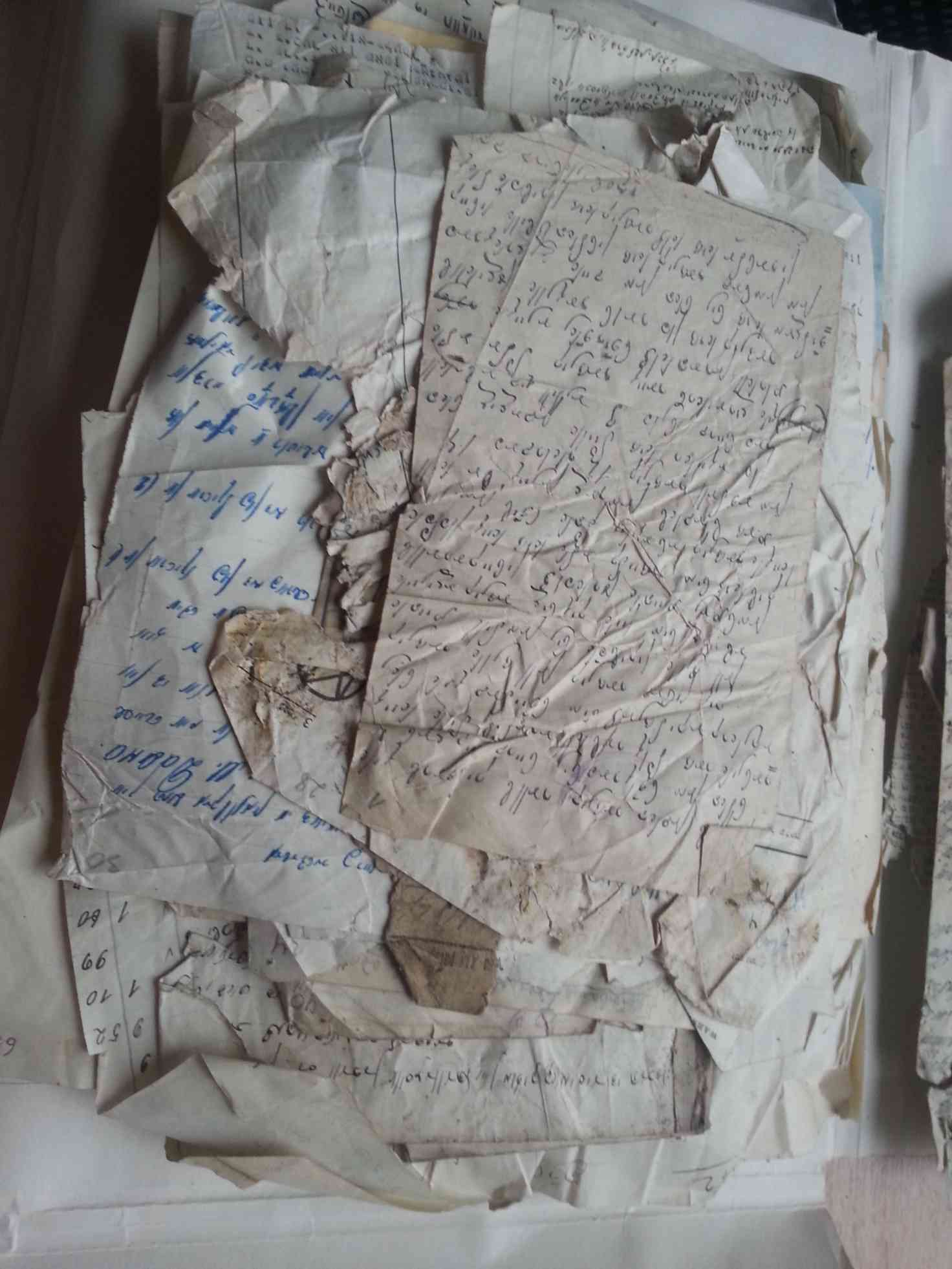

I came to work at the Book Palace [Book Chamber of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic] in 1951. I was nineteen, a first-year student. A year or so later circumstances led to me being appointed the temporary head of the Palace’s storage department. So our director Antanas Ulpis took me on a tour of all the properties I was to manage, all of the storage facilities containing sorted books and the church where the unsorted books were kept along with all the other riches brought in during the war, like homeless books, manuscripts and such. While showing me all those things, he also pointed out the hidden manuscripts of the Jewish archive, saying,“This is something you need to forget and never mention to anyone.”

Honestly, I was 21 years old and cared little about the manuscripts. I was more interested in books, so I did forget, although the occasion distinctly lingered in my subconscious.

I was not told and do not know how the Jewish archive came to be in the Book Palace. Generally, Antanas Ulpis was a man of great erudition. Everyone knows that before the war he had worked at the Culture Society, and had probably loved books since childhood, and that it was entirely due to him that ever since 1946, when he came to manage the Book Palace, books, manuscripts and other materials kept flooding in from all over the country.

The books were stored with us, although the purpose of the Book Palace was to store only books published in Lithuania and everything to do with the country: publications printed outside our republic, but mentioning Lithuania, or published in the Lithuanian language, or works by Lithuanian authors translated into other languages. All this was stored, inventoried, and sorted.

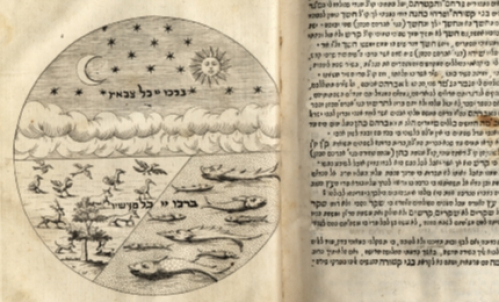

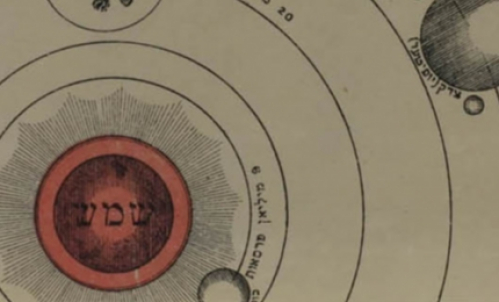

Any other publications were kept and catalogued only partially, not fully. Those included manuscripts. Manuscripts written in Lithuanian, Polish, or the like, were transferred to the state archives, or to the manuscript department at the Academy of Sciences.

Before I came to work at the Book Palace, Ulpis’ deputy was Isidor Kisin, a renowned Lithuanian bibliographer. Alongside him worked other members of the old intelligentsia: Feliksas Gailiskis, Antanas Biliunas, Vytautas Steponaitis for some time, and more — these were people who understood the necessity of books and manuscripts, and most likely contributed a great deal to the preservation of those manuscripts and everything else.

Perhaps one of the greatest paradoxes was that the Book Palace collected and kept books that were known as “special collection books,” that is, blacklisted books which were to be destroyed, burned. But due to the efforts of all these people, especially Antanas Ulpis, they were preserved in the Book Palace and there was even a special department, which we called our own “special collection,” for storing those books.

About 20 or even 30 years later, it transpired that the Book Palace had no permit to keep a special collection, that is, that department for storing blacklisted books. It appears that the Book Palace was methodically subservient to the USSR State Book Palace and book palace network; there were book palaces all over the country, and not a single one of them, not even the state one, had the right to keep a special collection book archive. So we preserved books which we in fact had no right to keep. But I must say that none of those who worked at the Book Palace and knew or surmised that these were publications and manuscripts of that kind ever said a word about the need to destroy them.

There was a time when the manager of the special collection was Michail Baron, a Jewish man. Perhaps it is not such a good idea to speak ill of a deceased person, but he previously worked at the Academy of Sciences library and had some books burned there. But as time passes, people change, and he must have changed as well, because when he came to work at the Book Palace and became the special collection manager, he already knew that burning books was very wrong, and despite the fact that he worked in an archive that had no right to exist, he nonetheless saved and preserved everything.

Antanas Ulpis was not a typical leader. He did the same work as his employees, and his contribution was even greater than everyone else’s. He spent every day, evening, and many a night at the Book Palace. For example, when the truck would come bearing books, it was usually late at night, there was often no electricity, and we would sit outside waiting for the truck. Antanas Ulpis would come unload the truck with the rest of us. We all carried the books to the storage room in candlelight like some sort of procession, shuffled along dragging stretchers full of books.

In addition, nearly every book and page that found itself in the Book Palace received Antanas Ulpis’ personal attention, and he went through each and every paper searching for Lithuanian print, Lithuanian publications, assessing their value. He understood the value of books very well, and he checked and collected them very thoroughly, while we merely sorted the books. Besides, it was directly due to Ulpis that the Book Palace was the first in the Soviet Union at the time that began consistently registering Lithuania-related print materials, that is, as I have mentioned, anything published outside the republic but mentioning Lithuania, Lithuanian authors etc., although the State Book Palace was strongly opposed to this work. They believed this to be an expression of nationalism and issued a ban on the project. The battle lasted about a decade, and finally Antanas Ulpis prevailed. He proved in many ways that this was a part of national culture which needed to be preserved, respected, and recorded, so that the knowledge and the information could remain for future generations.

This was the overall purpose of the Book Palace: collecting and storing every publication issued in Lithuania and outside it, in order to leave it all to the coming generations. For this reason, every publication that arrived at the Book Palace was stored exactly as published: in libraries, they were often lost, torn, or met similar fates, whereas the Book Palace preserved everything. It was the ancient dream of Lithuania’s bibliographers — to save all print material since the very first Lithuanian book, since the first Lithuanian publication, the first manuscript, etc., and books about Lithuania, for the people of the future.