Interview 1: E.R.

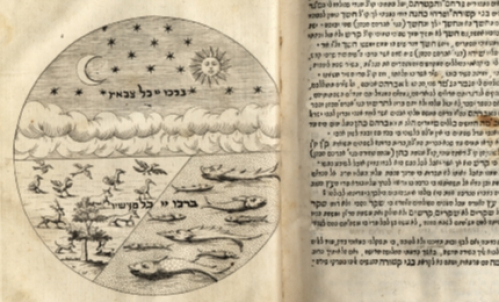

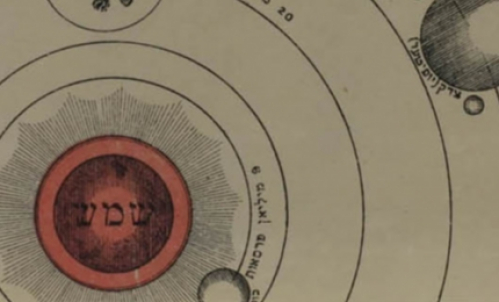

Antanas Ulpis was the former director of the Book Palace [Book Chamber of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic]. He took the position in 1946, after the Palace was founded in 1945. He was an outstanding bibliographer, a respected cultural figure, a wonderful organizer, a humane leader, and a lover and scholar of books. Almost his entire life had to do with books. It is due to his initiative that the former Book Palace (known since 1992 as the Lithuanian National Library’s Center for Bibliography) holds one of the major collections of Lithuania-related and Lithuanian print material, including Jewish studies and materials about Lithuania itself. It is probably the largest collection in the country.

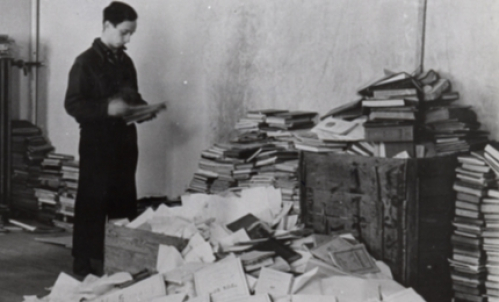

In Soviet times, it was not easy to collect forbidden materials, yet in the very first year of the institution’s existence Director Ulpis himself took some colleagues in a so-called “polutorka” truck around the country, collecting the scattered collections of libraries ravaged by the war, and the printed materials collecting dust in attics and garbage dumps.

The colleagues who worked and traveled with Ulpis remember his endless efforts to increase the collections of his institution, and to save unprotected books and printed materials, no matter in which language.

Personally, I met Mr. Ulpis somewhat later. In late 1955, as a seventeen-year-old girl fresh from my graduation exams, I came looking for a job. That was when I was hired to be a librarian. I remember well Director Antanas Ulpis trying to convince me to read Library Studies and Bibliography at the University. He promised to make it possible for me to combine studies and work. Having taken his advice, I graduated from Vilnius University in 1966, after completing a degree in Library Studies and Bibliography.In 1972, I became the manager of the National Print Archive.

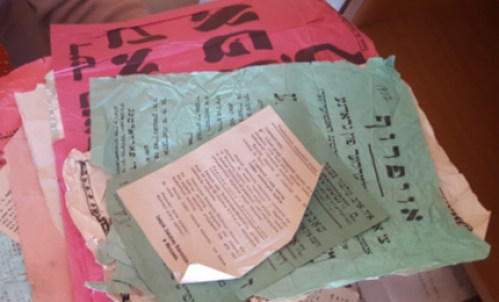

When Lithuania’s independence was restored in 1991, work began on sorting the collections amassed in the St. George Church. In the spring of 1994, a large pile of Soviet newspapers was being sorted, and when the pile was pulled aside and tidied, a stack of boxes showed up in the corner. They were varied in size, very dirty and torn, and once one had been opened we realized that a Jewish studies specialist was required. I immediately invited Ms. Alperniene to explain to us what this was, and Ms. Alperniene recognized the materials as YIVO Institute documents. We then realized these were important documents. (Initially, we had thought them to be minor papers, but were suspicious of the way they had been piled over.) We began examining them. There were several more people working on the issue, who even tried arranging the documents, and a few folders even came to be sorted this way.

Their physical state was terrible: crumpled, dirty pages; many of them torn, moldy, and wet. It was clear that the archive had survived only because it had been hidden. However, I do not know when, exactly, it was hidden.

173 boxes containing some of the remnants of the archival collections of the YIVO Institute (which had once been located in Vilnius) were uncovered.

When the archive was discovered, we reported it to the management, and on September 14 of the same year, I received the order that by agreement between the General Management of Lithuanian Archives and the Martynas Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania, the documents were to be transferred to the Lithuanian Central State Archive, to be stored with other manuscript materials. After the agreement, we began arranging them better, placing them in boxes, cleaning the boxes. Some employees of the National Archive arrived, and together with them we counted the boxes, tied and cleaned them.

All together we handed over 173 boxes. We had not counted how many had been found, but merely arranged them a little and merged several of the boxes.

It is my belief that Director Ulpis was a man to whom it did not matter what nationality a person was and in what language a book was written. Every little piece of print was equally important to him, and he taught us—what he taught himself: never pass by any piece of paper that has been thrown away. Besides, Antanas Ulpis probably saved this Jewish archive because there were many Jews in Lithuania. It has always been and is still known as the Jerusalem of Lithuania, so he wanted to preserve the archive in the faith that the YIVO Institute would be restored in Vilnius one day.

I do not know who brought the Jewish archive to our church or when it happened, so it is not clear to me who else may have helped rescue the archive. It is likely that the matter was known to Ulpis’ deputy at the time, the renowned bibliographer Isidor Kisin, who was Jewish.