Eddie Cantor: Portrait of an Artist as a Young Menace

by ALYSSA QUINT

“About thirty years ago, Morgn Zhurnal derived no nakhes from me. Does it have nakhes from me now?”

In 1957, the prestigious American publishing house Doubleday published Take My Life, the autobiography of the American Jewish comedian Eddie Cantor (né Israel Itzkowitz, 1892-1964). Cantor was a star of American radio and television and was best known for his comedy routines, vaudeville, and his performance in the Ziegfield Follies. After suffering a heart attack in 1952, Cantor retired and devoted much of his time to writing projects, including Take My Life, which he followed up with another volume of memoirs, The Way I See it (1959).

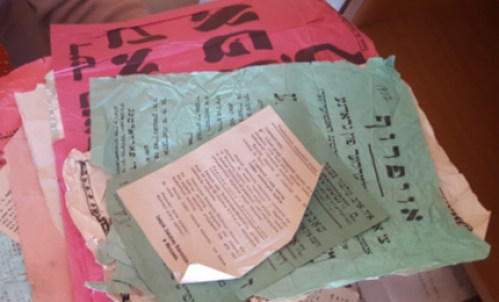

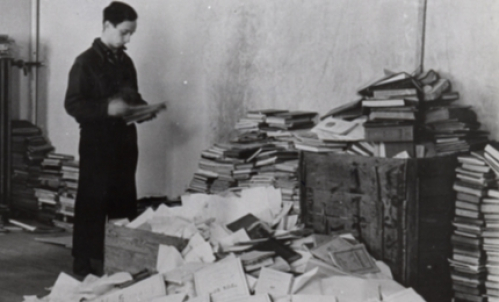

Only, Cantor had already published a memoir twenty years earlier. And he wrote it in Yiddish. Who knew? Well, the readers of New York City’s Yiddish daily newspaper Morgn Zhurnal (in English, The Jewish Daily) did. Based on current sources about Cantor’s life that make no mention of the serialized memoir, it was presumably forgotten about. Most of the installments of the twelve-part memoir were rediscovered, yellowed and tattered, earlier this year in a box of uncatalogued theater reviews and letters, in the Esther Rokhl Kaminska Theater Museum Collection, part of YIVO's Vilna Collections.

In contrast to Cantor’s English-language memoirs that focus on stories and anecdotes about his fellow Hollywood stars, his Yiddish-language memoir reveals more ample details about his childhood years, marked as they were by tragedy, but also resilience and humor. Cantor lost both his parents by the age of two, and his aged grandmother, Bubbe Esther, a smalltime matchmaker and door-to-door seller of notions, brought him up in a small tenement apartment on the Lower East Side. One installment of his Yiddish-language memoir records his father and grandmother's devastation over the death of his mother who died in childbirth. During the seven days of Jewish mourning, his father sat on the floor and read the Book of Job; his grandmother hired a professional kadish—someone to say the mourner's prayer for the year following her death—so as to hasten her son-in-law's return to regular life. Tragically, his father died a year later of pneumonia. As Eddie was so young when they died, he relied on his grandmother for the stories he provides about his parents. One installment features a picture of them smiling into the camera on an outing together to Coney Island.

But as one might expect, the memoir mostly ranges from charming to side-splitting. One installment begins with the following teaser, "When I went to public school, my arithmetic was not so great ("nit geven azoy oy-yoy-yoy"), but I recited poetry that was sublime (a mekhaye) to listen to.” The funniest installment might be the very first, one that also explains the appearance of Cantor's memoirs in Morgn Zhurnal as something other than accidental. He begins: "About thirty years ago, Morgn Zhurnal derived no nakhes from me. Does it have nakhes from me now?" Writing with intimacy to the newspaper’s readers, Eddie recounts how he grew up on Henry Street around the corner from the offices of Morgn Zhurnal. He explains that he used to play on the sidewalk in front of the newspaper's headquarters because he was always shooed away from the sidewalk in front of his own tenement by all the mothers with sleeping babies. One day he overheard two journalists from the newspaper talking about him, the noisy kid outside their window.

"Who is that young punk [shvartser boytshik]? ...What a young devil!"

"Oh him? He is a lunatic [a mushegener]," someone answered.

"Its little Eddie, a slow-progressing disease [a farshlepter krank], a two-bit comedian, a clown and big-mouth. He'll never amount to anything."

I overheard everything, but what did I care? I was having fun, what else did I need?

For the newspaper's Yiddish readers, the self-portrait of Eddie Cantor as a young menace might have recalled Sholem Aleichem's impish child narrator Motl from his literary masterpiece Motl Peysi the Cantor's Son, who is released from a world of discipline by his mother’s immigration to America and the coinciding death of his father. Motl’s iconic tagline is “Lucky me, I’m an orphan.” Cantor continues the story of his trouble-making throughout the installment:

On another occasion, a writer stormed out of the newspaper at his wit's end:

"Boy, what is the name of your father?"

"I have no father."

He became gentler. But he further demanded,

"What is your mother's name?"

"I don't have a mother."

Sadness stole into the eyes of the writer. He shook his head back and forth and kept repeating:

"An orphan, an orphan! Oy vey! Here, a few cents, go buy candy."

Cantor winks at his reader when he describes his shrewd use of his orphan status to escape punishment, and winks again at us when even his orphaned state is not enough to keep the journalists at the Morgn Zhurnal from trying to drive the young pest from the sidewalk outside their window. When, finally, an exasperated reporter demands the name of his grandmother, Eddie retreats: his grandmother was an avid reader of the Morgn Zhurnal and if she found out he was driving them crazy he would be in hot water with her. Young Eddie finally found a new play spot.

Eddie Cantor's Yiddish-language memoir awaits proper collation and—for non-Yiddish readers—translation. Its pages sparkle with his sense of humor and the pride he takes in his Jewish upbringing. And it appears alongside an advertisement for the Eddie Cantor rubber doll, all the proceeds of which, it was stated, went to charity. As was well-known to his fans—and what is made obvious in the pages of his memoirs in English and Yiddish—Cantor was as much a mentsh as he was a comedian, and that there is a deep connection between these two aspects of him.

The newspaper cutouts with Cantor's Yiddish memoirs were discovered in a box alongside another memoir, by one of the first female actors on the Yiddish stage, Chani Braginska. She acted under the founder of the Yiddish theater, Abraham Goldfaden, as early as 1880, when he discovered her and sent her to his parents' home in Old Constantine to improve her Yiddish. Neither of these historical treasures would have ever been rediscovered had these clippings not been sent to Vilna soon before World War II for preservation in YIVO's theater collection.

Alyssa Quint is YIVO’s first Vilna Collections Scholar. She has lectured and published extensively on Yiddish literature and culture. Her book on the rise of the modern Yiddish theater is forthcoming from Indiana University Press. On December 13, 2016, she will deliver a lecture on “The Yiddish Theater and America and Poland Between the Two World Wars” for the Ruth Gay Seminar in Jewish Studies.