The First Jewish Women Teachers

by ROBERTA NEWMAN

YIVO’s Uriel Weinreich Summer Program, the world’s oldest intensive Yiddish-language course, concluded its 51st session last week. Students from around the world spent six weeks in New York studying Yiddish and exploring the literature and culture of East European Jewry and its diaspora communities.

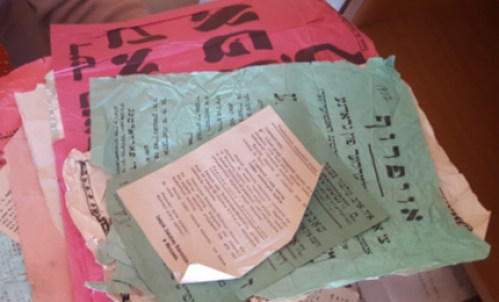

This year’s program is followed by a special workshop for teachers of Yiddish. The fact that many of today’s most revered teachers of Yiddish are women would not raise anyone’s eyebrows. But it wasn’t always this way. Two hundred years ago, Jewish women had to struggle for the right to work as teachers (or even to obtain an education), as attested to by these notes for a study on the subject. This document can be found in YIVO’s Collection on Yiddish Literature and Language (RG 3), which has recently been digitized for the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections project.

Sometime in the 1930s, Dr. Dina Yafe, a scholar based in Vilna, mined the Vilna State Archives for official tsarist-era documents about the first Jewish women teachers. One of the earliest accounts she came across was that of one Roze Rabinovitsh, from Minsk. In 1850, Roze petitioned the Governor-General of the province for the right to be admitted to a boarding school for upper-class girls. (There was no other high school for girls in Minsk.) But she was refused on the grounds that a Jewish girl simply wasn’t refined enough to study alongside the daughters of non-Jewish families.

However, the Rabinovitsh family didn’t give up. A year later, her father wrote to the Governor on her behalf. Please, he wrote. His daughter was very talented, but only in academic subjects. She had no “commercial talents” and he simply had no idea what was to be done with her since she was unsuited to start her own business. And she was depressed and sick over not being allowed to continue her education.

Lo and behold, this time the official in Minsk was supportive. In the intervening year, he’d gotten to know Roze and found that she made “a civilized impression” and wasn’t so different from “an upper-class girl.” The upshot was that Roze was admitted to the boarding school, and upon her graduation in 1855, took the teacher’s exam for the Minsk (boys’) high school. After that, Dr. Yafe writes, we have no more documentation and don’t know what became of her and her career. But in Dr. Yafe’s nine pages of notes, there are several other stories about early Jewish women teachers that she gleaned from the government archives.

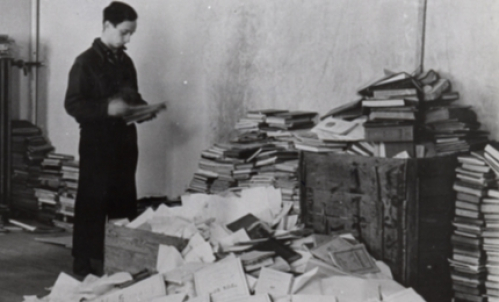

A graduate of the humanities faculty of Vilna University with doctorate in history, Dr. Yafe went on a few years after carrying out this research to become a member of the “Paper Brigade.” These courageous men and women were forced by the Nazis to sort through looted Jewish archives and libraries assembled at the YIVO building in Vilna, and risked their lives to hide as many treasures as they could, saving them from destruction.

Dr. Yafe was murdered in the Treblinka death camp. Her notes were among thousands of documents sent by the Nazis to Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany and recovered and sent to YIVO in New York after the end of World War II.