They Never Taught Us About This

by ROBERTA NEWMAN

Autumn 2017 marks one hundred years since the Russian Revolution. YIVO and other organizations around the world have organized panels and exhibitions on the subject and the Jewish press has devoted much space to essays and book reviews related to that anniversary, as well as to other watershed events that took place in 1917. The focus has been on the political and social effects of the Bolsheviks’ ascent to power and the establishment of the Soviet Union.

Less examined is the mass murder of Jews that took place during the brutal civil war which followed the revolution and the end of World War I. At least 50,000 (though possibly many more) Jews were murdered in pogroms perpetrated by White (anti-Communist), Polish and Ukrainian nationalist, Green (agrarian), and Red (Bolshevik) forces. While there had been earlier waves of pogroms, those that swept Ukraine, Belarus, and eastern Poland in 1919-1921 were unprecedented in scale. They hit a Jewish population already severely decimated and displaced, still trying to rebuild towns and communities which had been destroyed in the path of wartime battles.

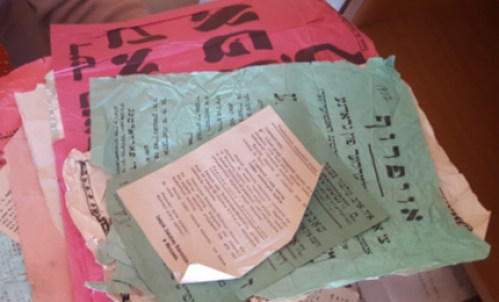

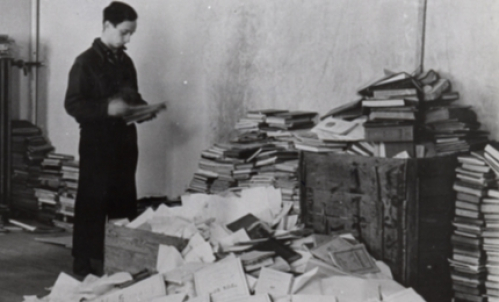

One of the world’s most extensive sources for the study of the 1919-1921 pogroms can be found in the YIVO Archives. The Mizrakh Yidisher Historisher Arkhiv (Archives for the History of Eastern European Jews) is the result of the work of Jewish scholars and activists who, even as the pogroms were still raging, set out to document them. Based in Kiev, the activists collected eyewitness reports, photographs, and other materials. Today, the part of this archive that survived the Holocaust is included in the Papers of Elias Tcherikower, which are being cataloged and digitized for the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Collections project.

Since many of the documents are in Russian, the main archivist for the Papers of Elias Tcherikower is Yakov Sklar, a native speaker of Russian and Ukrainian. For Sklar, who was born in 1974 in Kiev and emigrated with his family to the U.S. at age 18, the Tcherikower collections are an eye-opener. “They didn’t teach us about pogroms in school in the Soviet Union. I knew that my father’s grandmother was killed in a pogrom in a shtetl, but that was it. They said, ‘Oh, she was killed by Petlyura’ [Ukrainian nationalist leader held responsible for many of the pogroms]. But now I know that it was more complicated than that. The situation was so fluid – control of towns and cities changed hands from one day to another. She could have been killed by forces allied with Denikin [a leading White general] or even Bolsheviks. All sides in the conflict had bands of pogromtshiks who killed Jews.”

One day, Sklar came across a document that hit particularly close to home: a building-by-building list of people injured in a pogrom in Kiev. He was stunned to see the address of the building he lived in as a young child. “At least, there was no one on the list who lived in our actual apartment,” he reports. “No one ever talked about this in Ukraine. There has been no national reckoning in Russia or in the countries of the Former Soviet Union about the Jews murdered en masse one hundred years ago at the hands of thugs and with the complicity or encouragement of leaders.”

Today, few Jews anywhere in the world know much about the catastrophe of World War I and the 1919-1921 pogroms. The even greater cataclysm of World War II and the Holocaust has largely erased the earlier trauma from Jewish collective memory.

The Tcherikower Papers also include in-depth materials on other aspects of Russian and Ukrainian history. “Another thing that people tend not to realize,” Sklar points out, “is that archival collections at YIVO offer more to historians and scholars than just Jewish history. They are an often overlooked resource for the study of Russian history, in general.” For instance, among the sub-collections of the Tcherikower Archive are the Papers of Marc Ratner (1871-1917), one of the founders of SERP (Jewish Socialist Workers' Party), an anti-tsarist organization. Sklar finds particularly interesting a letter sent to Ratner by Boris Savinkov, a leader of the Socialist Revolutionary Party famous for being responsible for assassinations of tsarist officials. “He was an early example of a terrorist,” Sklar notes.

Another collection he is processing are the Papers of Maxim Vinawer (1862-1926), a lawyer and founding member of the Constitutional Democratic Party of National Liberty in Russia, which called for a parliamentary government based on the British system. He was a delegate to the first Duma in 1906. “He was also a friend of Vladimir Nabokov’s father,” Sklar adds with a laugh.

Roberta Newman is YIVO’s Director of Digital Initiatives.