To Change the World with a Dictionary

by ROBERTA NEWMAN

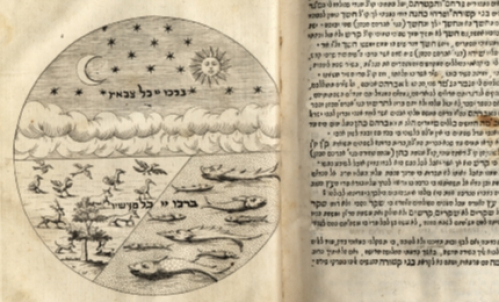

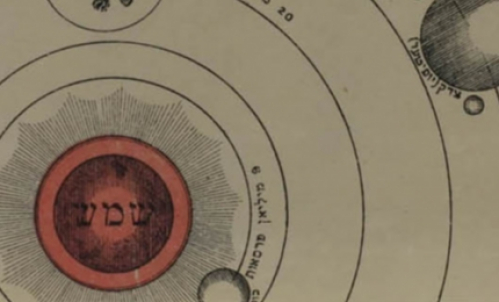

A dictionary doesn’t seem like it would have much potential to be revolutionary, but this “German”-Hebrew dictionary was, in its time, a bold statement of the Haskalah, the 18th-19th-century reformist intellectual movement that is often referred to as the Jewish Enlightenment.

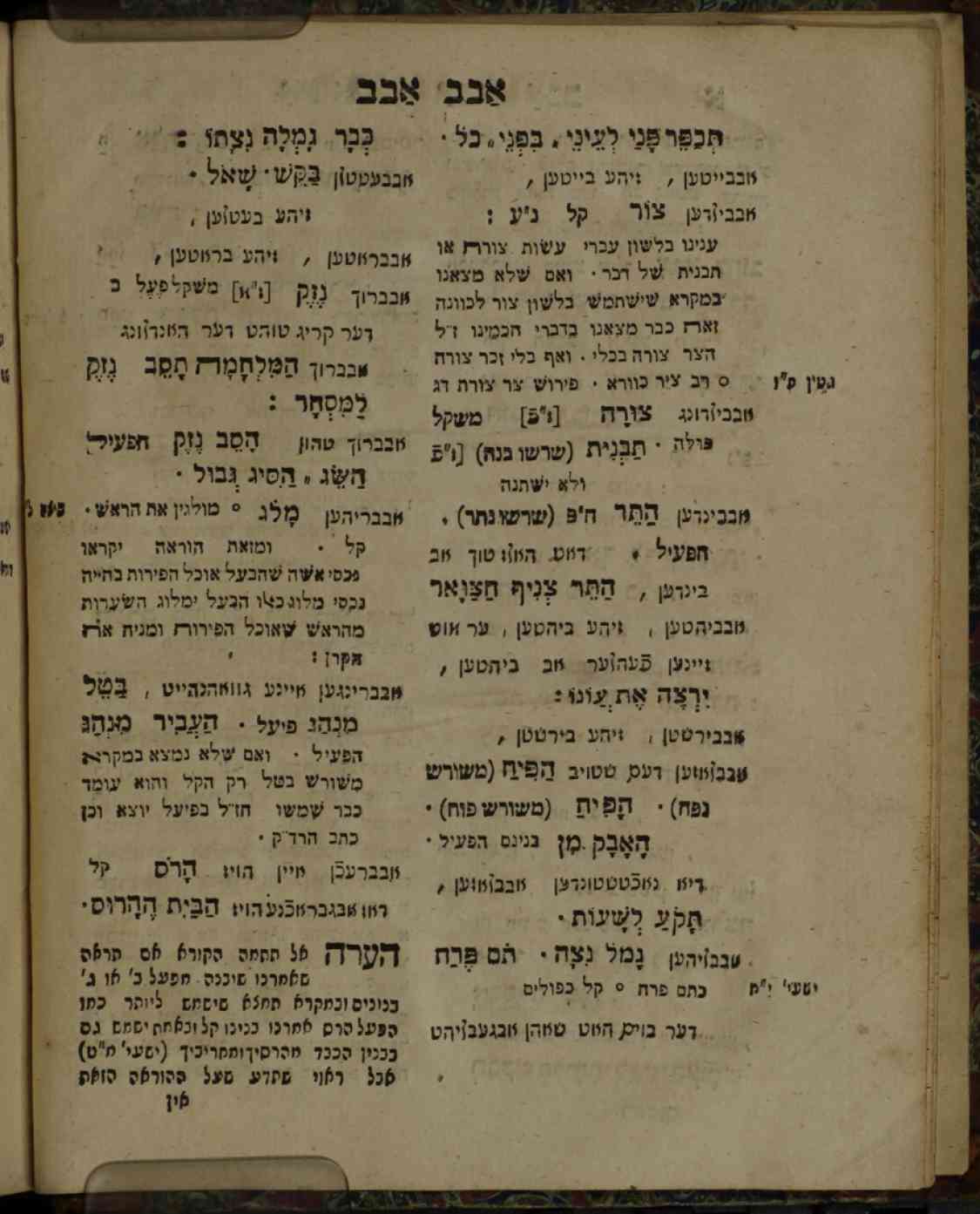

The stated purpose of Netiv lashon ‘ivrit (Path of the Hebrew language) was to teach Jewish children Hebrew. The anonymous author imagined the book being put to use in Jewish schools. There is no year of publication noted but it is believed that this book was printed in Dyhernfurth, Prussia (presentday Brzeg Dolny, in southwestern Poland) in the late 18th century. The town had a long tradition of Jewish printing. The dictionary only goes up to letter “G” and it isn’t known if any additional volumes were ever published.

This book follows in the footsteps of leading light of the Berlin Haskalah Moses Mendelssohn’s 1783 translation of the Pentateuch (the Torah) into German, Netivot ha-shalom (Paths of Peace), which had Hebrew text and the German translation (in Hebrew letters) printed side by side. The “Path” in the title Netiv lashon ‘ivrit was likely an homage to Mendelssohn.

How could Hebrew and translation of the bible be considered revolutionary – a challenge to tradition and to the authority of the rabbinical establishment? The maskilim (reformers) sought a new emphasis on the Torah, whose universal human values were a link between Jews and the wider world. Knowing Hebrew was a key to being able to read this text unmediated by rabbinic authorities.

Hebrew was considered a noble language and a link to the glorious Jewish past. The maskilim, by and large, disdained Yiddish as a worthless jargon, a non-language. They promoted not only Hebrew but also the acquisition of elite European languages such as German and Russian. German in Hebrew characters, sometimes referred to as Judisch-Deutsch, was seen as a way to wean Jews away from Yiddish. It might look like Yiddish, but, in fact, was a type of “anti-Yiddish.” For readers in the Russian Empire, where this copy of the book ended up, the side by side text provided an opportunity to learn both German and Hebrew.

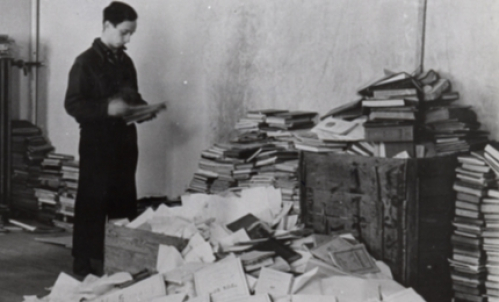

The book is extremely rare (there are less than half a dozen known copies in libraries around the world). This copy was part of the private collection of Matisyahu Strashun (1817-1885) an important book collector, who amassed about 6,000 books over the course of his lifetime. He bequeathed his collection to the Vilna Jewish community, which used it as the basis for a public Jewish library, which soon became one of the great Jewish libraries of Europe. The book may also have been previously part of a library in Radoszkowice (presentday Belarus), as attested to by the Russian inscription on the title page, which notes that the book was cleared by the rabbinate of Radoszkowice for the Russian censor in 1838.

Roberta Newman is YIVO’s Director of Digital Initiatives.