Translated and Improved

by Alyssa Quint

A favorite phrase about Yiddish translations of Shakespeare's plays is “ibergezetst un farbesert” (“translated and improved”). It’s not that the translators who used it didn’t respect the artistic heights of Shakespeare’s work. Rather, this cadre of translators—most of them translating for New York’s Yiddish stage in the first decade or two of the twentieth century—had less interest in parsing the poetic beauty of Shakespeare’s lines, and more interest in distilling an entertaining Yiddish-language version of a play with which to pack Yiddish theater houses. The phrase inevitably meant that the play was translated and not improved upon. In fact, it was probably translated and rendered worse, sometimes egregiously worse, than the original.

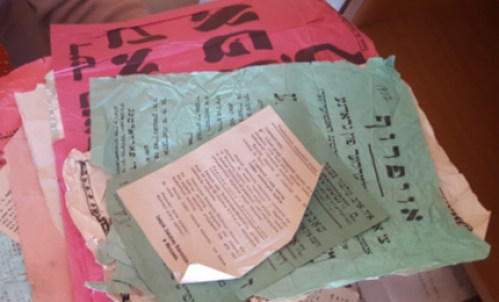

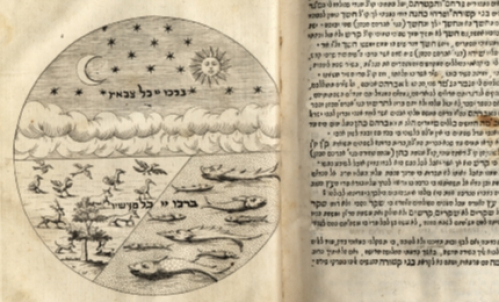

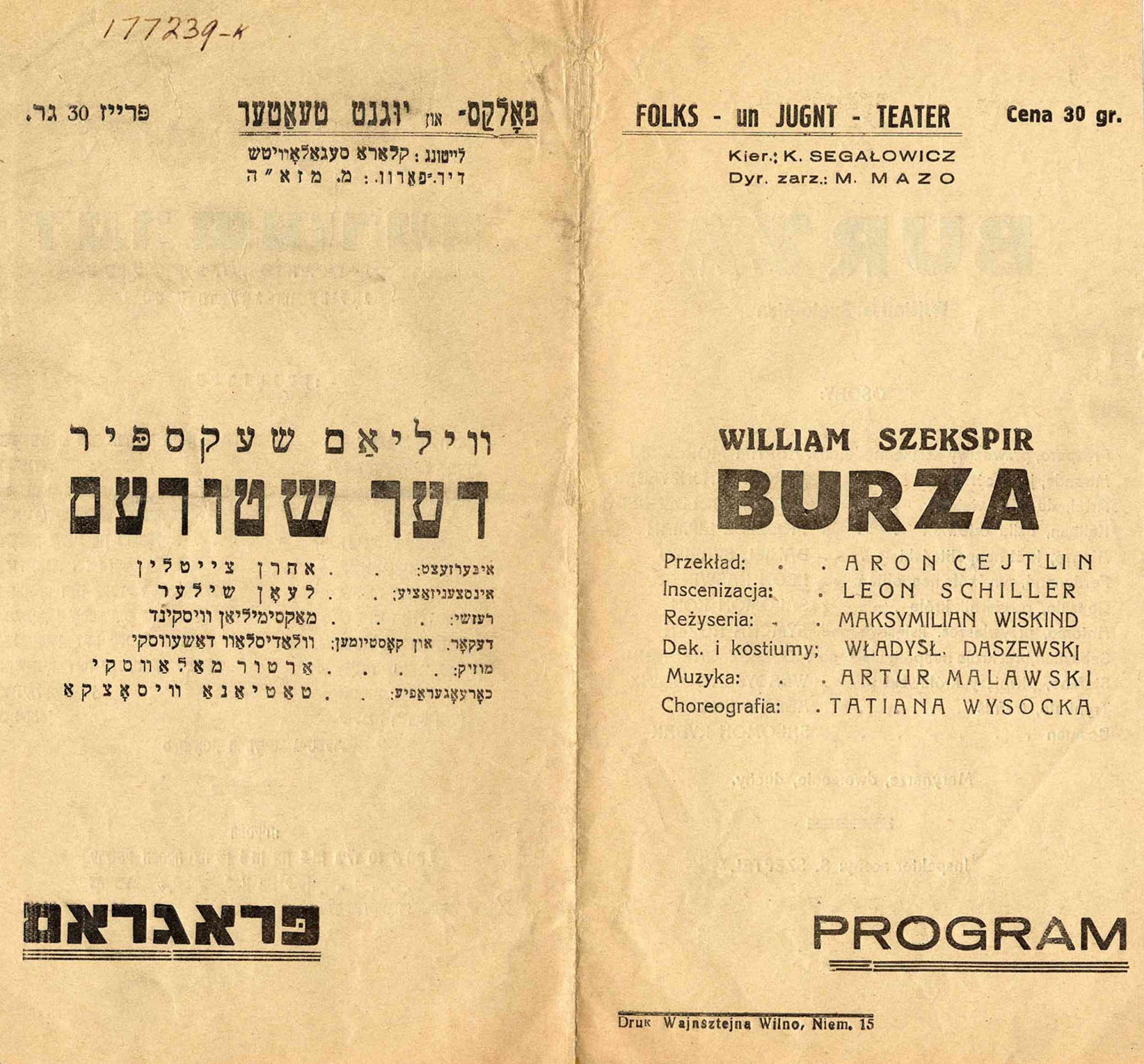

staging of Aaron Zeitlin’s Yiddish translation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest by celebrated director

Mordkhe Mazo, c. 1930. YIVO Archives.

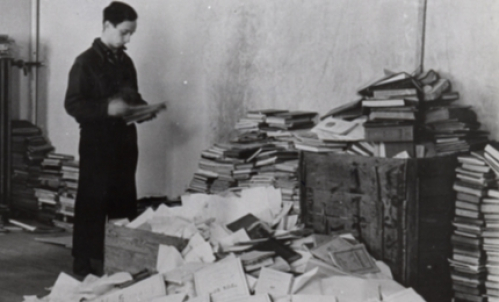

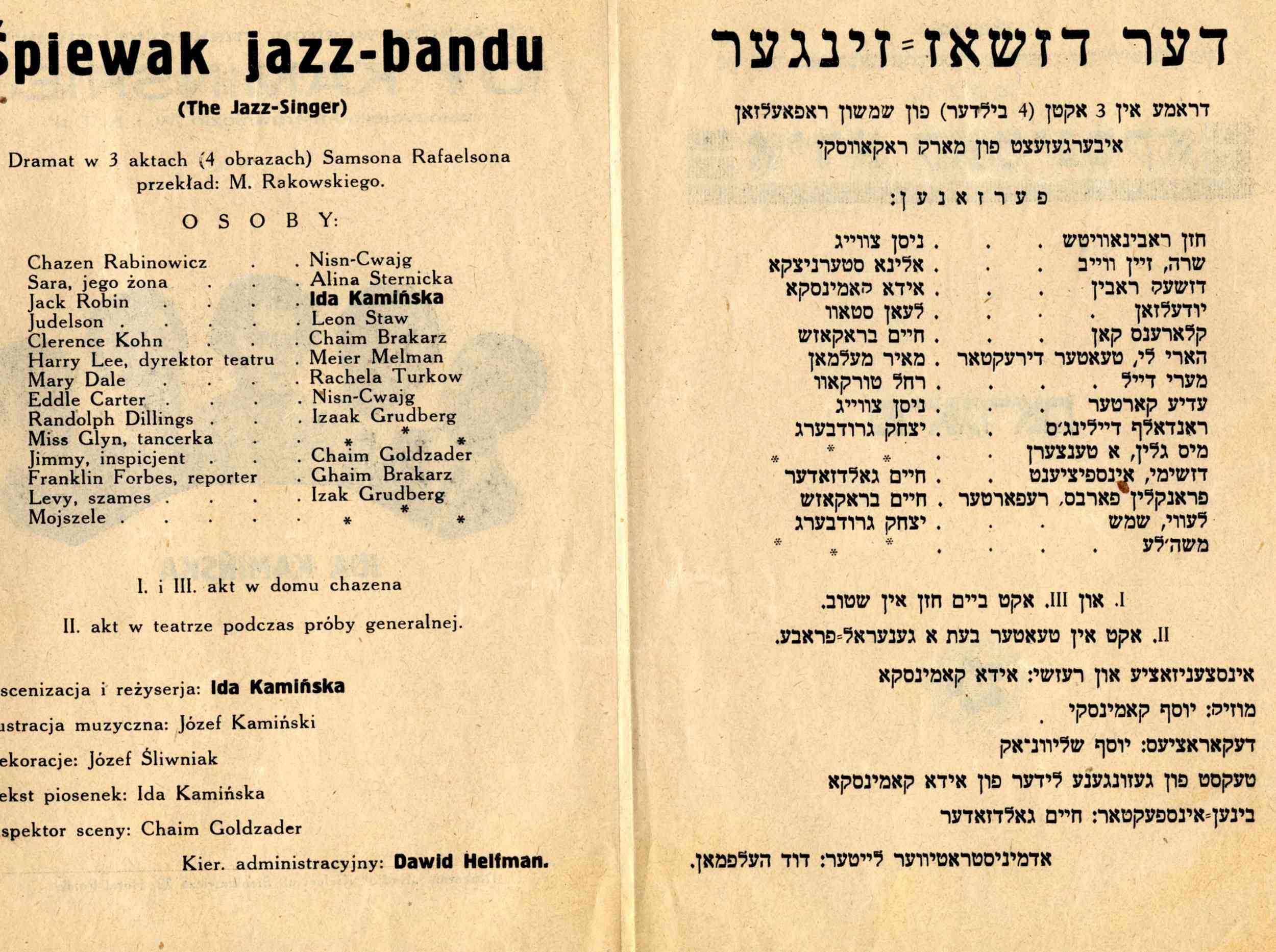

However, “the translated and improved” phenomenon accounts for only a tiny fraction of translations undertaken for the Yiddish stage. Thousands of surviving programs and placards in YIVO’s Esther Rokhl Kaminska Theater Museum Collection (part of the Edward Blank Vilna Collections), reveal the centrality that translation played, especially during the interwar period, the Yiddish theater’s most fruitful and creative decades. In Warsaw in the 1930s, for instance, you would have been able to catch the visionary actor Ida Kaminska’s (1899-1980) staging of the American The Jazz Singer, in which she herself performed the title role, cross-dressed and in blackface, as well as a Yiddish rendering of Shakespeare’s The Tempest (Der shturem), in a translation by none other than the literary modernist, Aron Zeitlin (b.1898). On a given evening in Vilna during the same period, you might take in the Jewish Opera’s Yiddish version of Puccini’s Tosca or Zalmen Zylbercweig’s (1894-1972) Yiddish rendering of Ibsen’s Ghosts. The long list of translations on the Yiddish stage reveals how thirsty Yiddish players were to broaden the theatrical vocabulary of the Yiddish theater, to stretch its emotional and cultural reach, and demonstrate its ability to contain cultural multitudes.

The important presence of translated works on Yiddish stages throughout Poland and America during this era does not reflect a shortage of native Yiddish imagination. Quite to the contrary, it is revealing of how important translation is to the creative foundation of a given language. Translation allows translators a unique communion with a fellow playwright—it lets the inspired and inky words of the original author flow through his pen—and it allows direct participation in his project. For some in interwar Poland, the act of translating was also an extension of their politics and an extension of their acting. The avant-garde actor Zygmunt Turkow (1896-1970) acted in his own translations of a number of works including one by the Nobel-prize-winning French pacifist and playwright Romain Rolland. In general, interwar Yiddish culture coincides with the least insularity in Yiddish culture, its most confident and expansive time.

In the vision of the participants of Yiddish theater of this era (who were almost all multilingual and prided themselves on their worldliness) translation created cultural bridges through which creativity traveled in both directions.

Yiddish language adaptation of The Jazz Singer, translated and directed by Ida Kaminska.

The most important example is S. An-ski’s (1863-1920) The Dybbuk, a work that itself coalesced from Yiddish, Hebrew, and Russian, and played in many languages in the wake of its explosive first Yiddish run. The Polish-Jewish playwright Mark Arnshteyn (Andrzej Marek, 1879-1943) is another. He translated and directed his own works for the Yiddish stage and translated Yiddish works for the Polish stage, including H. Leivick’s (188-1962) The Golem. Translation brought Yiddish theater into conversation with theaters and studios of other languages so that trends of staging, set design, and acting technique flowed freely across linguistic borders.

Minyatur teater (miniature theater), a genre of Yiddish performance that was indebted to both Polish and Russian literary cabaret as well as traditional forms of Jewish performance, often featured translated works where Yiddish creativity was wedded closely to works of non-Yiddish and non-Jewish artists. In one surviving program from a performance of miniature theater in Vilna, a sonata by Bach is the backdrop to the recitation of a poem by the poet Sore Reyzen (1885-1974); in another, a song from Meyerbeer’s opera L’Africaine follows an excerpted scene from Sholem Asch’s (1880-1957) God of Vengeance. Translated works situated the Yiddish theater in the context of current and classical works of creativity. There was nothing that could not be dramatized in Yiddish.

For some, a focus on the winking phrase of “translated and improved” summarized what they understood to be the ironic, self-deprecating modality of Yiddish. But, really, this one-dimensional view of the language is a product of Yiddish’s post-vernacular condition, by English-speakers who generated a narrow explanatory box in which to lay to rest the language of grandparents. It is translation as an act of cultural narrowing, rather than cultural expansion. Better to say, I suggest, without the irony that clings so readily to Yiddish: ibergezetst un farraykhert (translated and enriched), ibergezetst un farshtarkt (translated and strengthened) and, yes, seriously, ibergezetst un farbesert (translated and improved).

Translated works include those by the following group of diverse playwrights:

- Molière (French)

- Emmerich (Imre) Kálmán (Jewish-Hungarian)

- Henrik Ibsen (Norwegian)

- Theodore Dreiser (American)

- Eugene O’Neill (American)

- Leonhard Frank (German Expressionist)

- Ladislaus Fodor (Jewis-Hungarian)

- Antoni Cwojdzinski (Polish)

- Leopold Falls (German)

- Jan Fabricius (Dutch)

- Arthur Schnitzler (Austrian)

- Maxim Gorky (Russian)

- Edward Sheldon (American)

- Alexandre Bisson (French)

- Gerhart Hauptmann (German)

Alyssa Quint is YIVO’s Scholar-in-Residence of the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Collections.