What Was Considered Funny Two Hundred Years Ago?

by ROBERTA NEWMAN

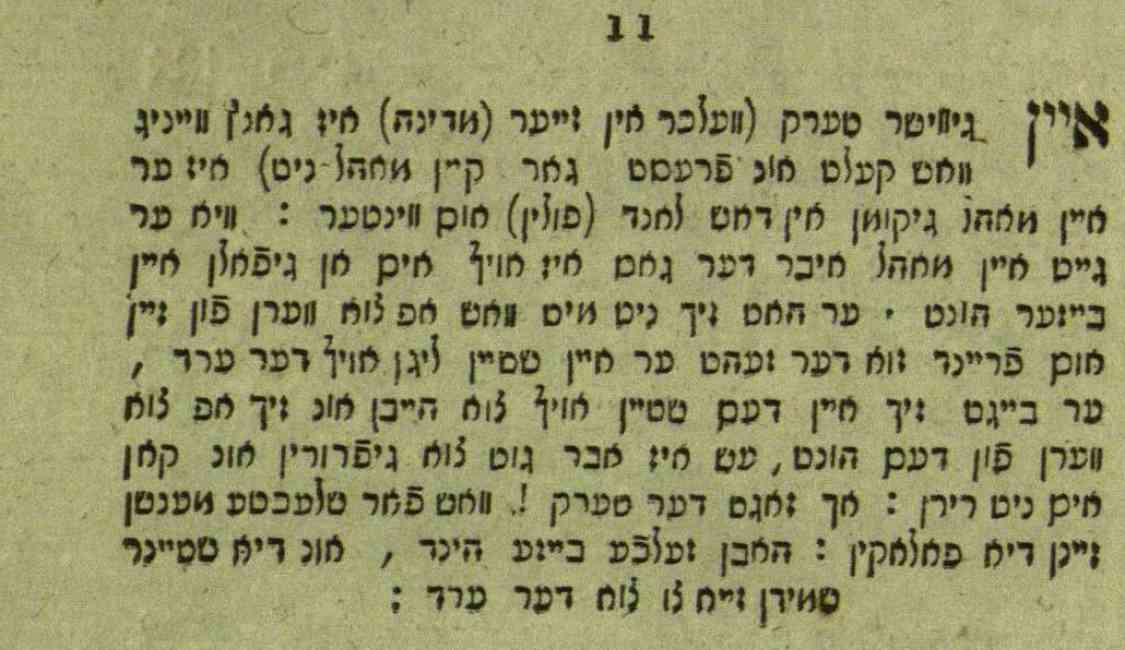

A certain Turk, who had hardly ever experienced cold or frost in his native land, arrived in Poland, in the wintertime. Once, as he walked on the street, he was fallen upon by an angry dog. He had nothing with which to drive away his adversary and so, seeing a stone lying on the ground, he bent down to pick it up. But it was well-frozen to the ground and he couldn’t budge it. “Ach!” said the Turk. “What sort of terrible people are these Poles. They not only have such angry dogs, but they also forge the stones to the ground.”

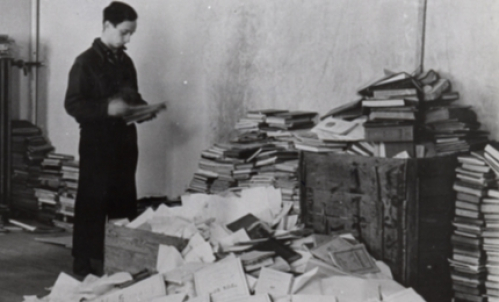

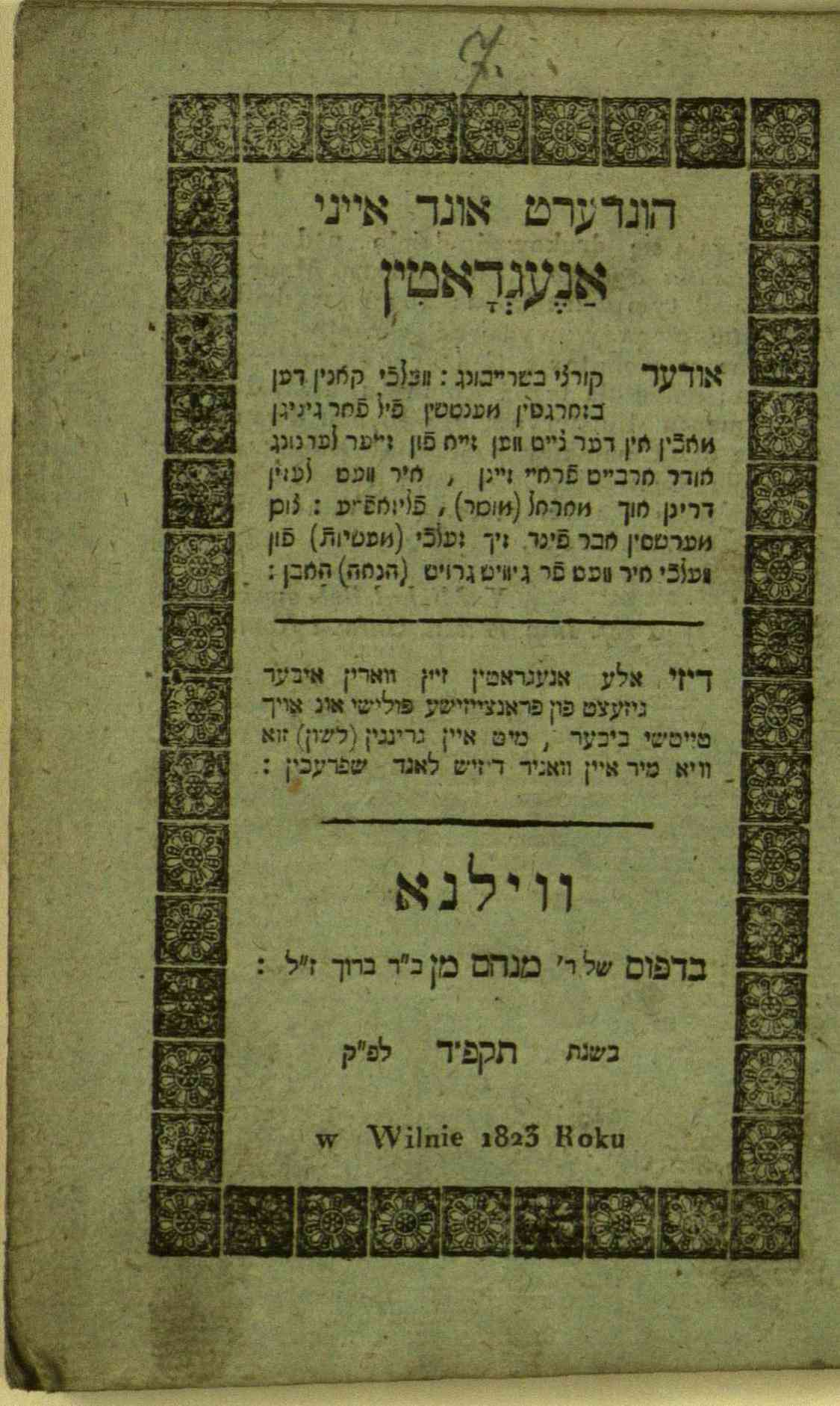

Among the early nineteenth-century books digitized for YIVO’s Vilna Collections Project at the Martynas Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania is an anthology called Hundert un eyni anekdotin (One Hundred and One Humorous Anecdotes), published in Vilna in 1823.

The blurb on its title page notes that most of the anecdotes are translations from French and Polish into an “easy to understand” Yiddish “as spoken by those who live in this country.”

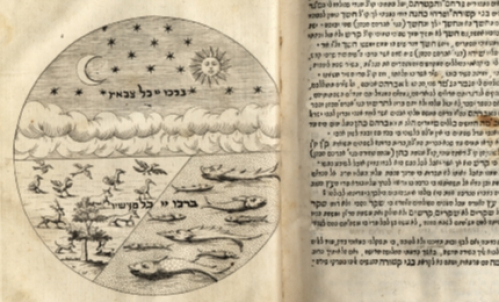

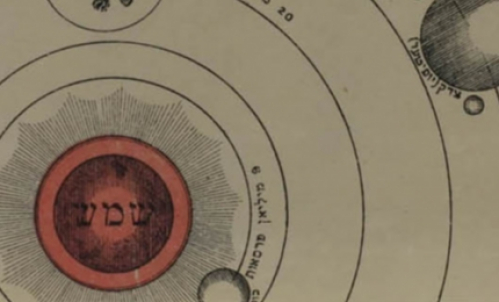

It was a time when there was not that much available to read in Yiddish. The great blossoming of Yiddish literature of the late nineteenth century was still a couple of generations away and the most common Yiddish reading matter was the tsene-rene (adaptations of stories from the Bible); other religious books, especially ethical literature (musar); and a few translations of epic tales, such as Elye Bokher’s oft-reprinted Bove-bukh, first published in 1541.

Though all of these Yiddish genres were intended primarily for women, there is much evidence that men, too, read Yiddish books, especially those who were not well-educated enough to read rabbinical works in Hebrew. In reality this encompassed a broad segment (perhaps the majority) of the male Jewish community.

Hundert un eyni anekdotin is unusual for a Yiddish book in appealing openly to a male readership even as it preemptively counters the charge that it is bitl-zman (a waste of time better spent studying Torah). It promises to “give great pleasure to the anxious person when they have a free moment from their studies or work” and sought to place itself within existing categories of Yiddish literature by claiming that its pages included passages of musar.

In any case, the “anecdotes” function as proto-jokes, replete with punch-lines. By today’s tastes they wouldn’t be considered funny or politically correct. The butts of the joke are often foreigners, lower-class types such as peasants, and women. Here is one that turns on a pun and is set during the Battle of Minorca, a famous 1756 naval battle between the British and French during the Seven Years’ War:

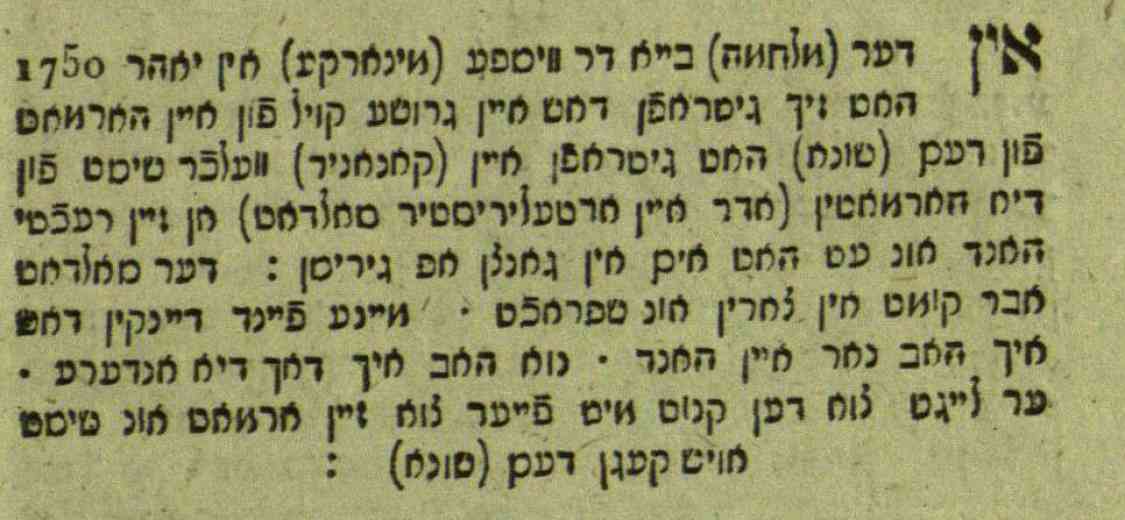

In the war at the [Vispa?] (Minorca) in 1750 [sic], a huge cannonball shot from the enemy’s cannon hit and completely tore off the right hand of a cannoneer (or an artillery soldier) who was shooting from the vicinity of the cannons. But the soldier fell into a rage and said, “My enemy should be thankful that I only have one hand. Nu, I still have one left.” He ‘lent a hand’ to the lighting of the wick of his cannon and shot at the enemy.

Roberta Newman is YIVO’s Director of Digital Initiatives.