Chaim Grade and the World of Lithuanian Jewry: Interview with Curt Leviant

by LEAH FALK

Curt Leviant is an esteemed translator, Yiddish scholar, and fiction writer. Among his translations are five volumes of Sholem Aleichem’s work, Chaim Grade’s The Agunah and The Yeshiva, and books by Avraham Reisen, Lamed Shapiro, I.B. Singer, and fabulist Eliezer Shteynbarg. Several of his seven critically acclaimed novels have been translated into major European languages.

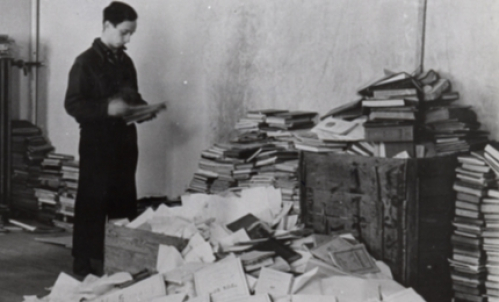

For YIVO’s Winter Program, Leviant will teach a course on Yiddish Romantic poet Chaim Grade (1910-1982), “Chaim Grade and the World of Lithuanian Jewry.” In 2013, YIVO acquired Grade’s archive, including 20,000 volumes in multiple languages. (For more information on this acquisition, click here).

I asked Leviant about the challenges of presenting Grade in English, the differences between Grade and his famed contemporary I.B. Singer, and how the poet represented both religious and secular life in his writing.

In 2011, writing about translating Chaim Grade, you said “In

[translating him], I came to understand that this actually required

knowledge of four languages: not only Yiddish and English, but also

Hebrew and Jewish.” Many readers recognize that Jewish literature is

often necessarily multilingual. In what ways does Grade’s work embody

this notion? What’s unique about his work in this respect?

Well, the English part refers to the ability of the translator to transmit the original into elegant English. To make it sound as if the text were actually written in English.

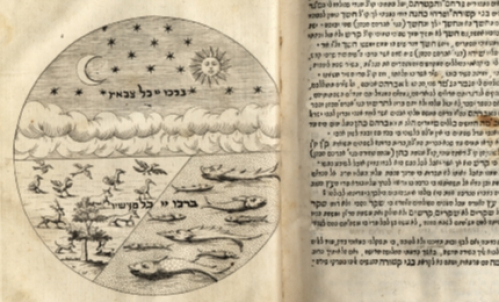

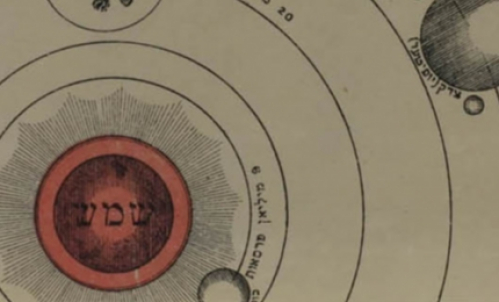

The Hebrew part is easy -- for Yiddish has a roughly 18-20% Hebrew content. But the Jewish part is more difficult, the most difficult, and this is where translators stumble. For translating from Yiddish, especially Chaim Grade, entails knowing the entire Jewish tradition (mostly Hebrew) from a religious point of view.

When you read Chaim Grade's The Agunah or The Yeshiva, one must know the daily religious tradition, be familiar with the sacred texts, Bible, Mishna and other post-Biblical books, be able to catch the nuances of connections to traditional Jewish life even in throwaway remarks.

In both The Agunah and The Yeshiva rabbis discuss Talmud and halakha (Jewish law) and cite quotes from rabbinic sources. If one only knows “Yiddish Yiddish” and not “Jewish Yiddish” those passages will be Sanskrit to them. Moreover, in The Yeshiva, when rabbis are discussing sacred texts among themselves their Yiddish will be 90% Hebrew, with just an "at" or "that" and perhaps an "and" in Yiddish.

Your course will be taught in English. How will you approach

teaching in English a writer who accesses so many different languages

and cultural fluencies in his work?

We will be using texts by Grade where the translator is thoroughly familiar with every nuance of every language that Grade uses -- especially the Jewish language.

Grade was a promising yeshiva student who left the world of Jewish study to become a writer. What do you think was most interesting about the play between traditionalism and secularism in his life and writing?

Yiddish writers (almost all of whom grew up within the Jewish tradition) who left traditional Jewish life almost always had a slightly negative tone toward the tradition they abandoned. Chaim Grade, on the contrary, although admittedly a secular Jew, speaks fairly about both sides. His marvelous story “My Quarrel With Hersh Rasseyner,” which we will be reading in the course, is a classic example of this balance. He represents both the rigorously Orthodox speaker (Hersh) and the secularist (Chaim) in perfect balance, giving the most cogent arguments for both sides.

In your Winter Program course, you’ll be reading Grade alongside some of his contemporaries, such as I.B. Singer. What do you see as the main difference between Grade’s and Singer’s approaches to Eastern European Jewry?

First of all, Singer is from Warsaw and Grade from Vilna, and there were religious Jews and roughnecks in both cities. But although both were about the same age (Singer, born in 1904, was six years older) Singer is one generation removed from the religious tradition. His father was a rabbi and Grade was a yeshiva bokher until he left the house of study and could have had rabbinic ordination.

We will read a few of Singer's memoir/stories, where the young Singer eavesdrops (standing out of sight behind a bookcase) on his father's rabbinic court wherein he renders decisions or gives advice, and compare it to the way rabbis in Vilna make decisions.

We will also peek into daily life in the yeshiva: one portrait by an older contemporary of Chaim Grade, Lamed Shapiro; the other, by Grade himself from his masterwork, The Yeshiva.

Singer and Grade were obvious rivals, with Singer delving into folklore and myth and magic and the fantastic, and Grade the super-realist, writing as if he were tape recording people in every level of Vilna's Jewish society.

Who would most enjoy this course?

Good question. Someone literate who has either tasted a bit of Chaim Grade and wants to read more, or someone who has heard about Grade and would like to experience almost first hand the work of a writer who so faithfully creates and re-creates the men and women of Vilna, the rich and the poor, the scholarly and the untutored, the kind and the mean, with such poetic power that you feel you are in Vilna, in the street, in the synagogue, in the synagogue courtyard, in the marketplace.

Reading Chaim Grade you feel you are a camera witnessing real life unfold before you -- a life that was suddenly cut off when the Germans marched into Vilna and destroyed everyone and everything in it.

We will read fiction which is as true as memoir and Grade's Holocaust memoir which is as true as poetry and as vivid as fiction.

Leah Falk is YIVO’s Programs Coordinator.